From Cal Poly to the Moon: How an Engineer Captured America’s First Views of the Lunar Landscape

On a summer night in 1966, as the United States attempted its first soft landing on the moon, Cal Poly engineering graduate Donald Montgomery monitored the mission from the Goldstone Deep Space Communications Complex outside Barstow, California. As the lead designer of NASA’s Surveyor 1 camera system, he was fully aware of the historic potential of this moment in the space race.

Montgomery and his two Jet Propulsion Laboratory colleagues felt the tension mount as the robotic spacecraft made its final descent toward the lunar surface.

This mission marked the U.S.’s first attempt at a soft landing, which involves gently settling the spacecraft on the moon to keep its delicate instruments intact for quality data collection. Success meant that Montgomery’s camera system could capture unprecedented images, setting the stage for future human missions and opening a new chapter in space travel.

Yet, despite meticulous preparations, the outcome was far from certain.

“We weren’t terribly optimistic that it would work the first time out of the bag,” Montgomery said with a chuckle, recalling how their testing, which involved dropping models from balloons, couldn’t adequately simulate the moon’s low gravity.

Thus, it was with a mix of skepticism and awe that Montgomery and his colleagues watched as Surveyor 1 approached the surface, 63 hours after its launch from Cape Kennedy aboard the Atlas-Centaur. As the landing gear unfolded, the spacecraft’s tripod frame and massive footpads became stark silhouettes against the lunar void.

“Once we started seeing it was doing what it was supposed to do, we looked at each other and said, ‘Holy moly, this damn thing might actually land!’” Montgomery recounted.

In fact, Surveyor 1 executed a flawless three-point landing in the moon’s Ocean of Storms that very night, June 1, 1966, leaving the engineers astonished and the world captivated.

“It was a profoundly emotional experience, and simultaneously, a spectacle of absolute beauty,” Montgomery said. Now at age 93, he continues to reflect on those pioneering days, gaining a deeper appreciation for how his camera system shaped space exploration.

* * *

Montgomery earned his degree in electronic and radio engineering in 1952 from Cal Poly, where he embraced the Learn by Doing philosophy.

“Cal Poly was instrumental in honing my ability to dive into a project, learn from it and move forward,” he explained.

Montgomery began working at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in 1962, quickly becoming familiar with space-based television systems. The following year, he was selected to lead the development of the camera system for Surveyor 1, which was designed and built for NASA by the Hughes Aircraft Co., under the technical direction of JPL.

Montgomery recalled the urgent atmosphere that followed the Soviet launch of Sputnik in 1957, Earth’s first artificial satellite. The event had ignited the space race, spurring the U.S. into a fervent push to prove its technological prowess and regain prestige in the global arena.

“NASA was deeply committed to placing a soft lander on the moon, aiming to make a significant leap toward human lunar exploration,” he said, noting that the landing site for Surveyor was also being scoped as a potential site for the Apollo missions.

Engineers, including Montgomery, labored around the clock to prepare for the first deployment of a science-oriented television camera that would map the moon’s landscape, focusing on features like craters, rock formations, colors and light – critical elements for understanding the surface.

Developing the camera system for Surveyor 1 presented significant obstacles, including ensuring it could withstand the extreme lunar temperatures, operate effectively in the low-gravity environment and deliver high-resolution images across the vast distance back to Earth.

Overcoming these challenges made the moment all the more thrilling for Montgomery, stationed at the Goldstone site, when the first images – processed in real time by a scan conversion system – began to appear on the monitors, unveiling the lunar surface with extraordinary clarity.

“It was exhilarating to see those images unfold until they filled up the entire screen,” Montgomery recalled, his voice softened by awe as he shared the memory.

* * *

In the initial days following Surveyor 1’s landing, Montgomery and his team transmitted commands to JPL’s space operations building in Pasadena, directing the spacecraft to capture the specific images of lunar soil and data on surface composition necessary for scientific analysis.

During its extended mission on the moon, Surveyor 1 captured and relayed over 11,000 photographs along with detailed data on surface textures and temperature variations. By its 42nd Earth day, it had achieved the unexpected – withstanding extreme temperatures ranging from 250 degrees Fahrenheit during the lunar day to minus 260 degrees Fahrenheit during the two-week-long lunar night.

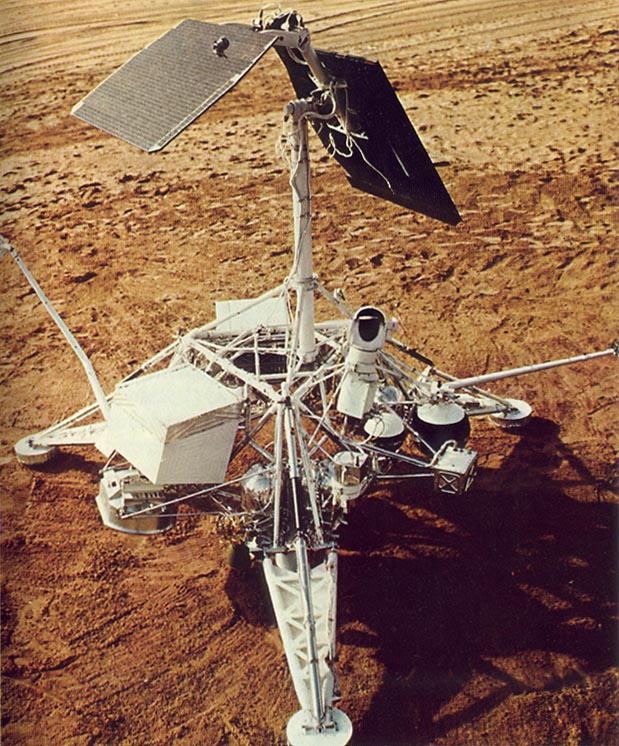

A model of the Surveyor probes is shown in the California desert. Early testing involved dropping models from balloons, which couldn’t adequately simulate the moon’s low gravity. Credit: NASA

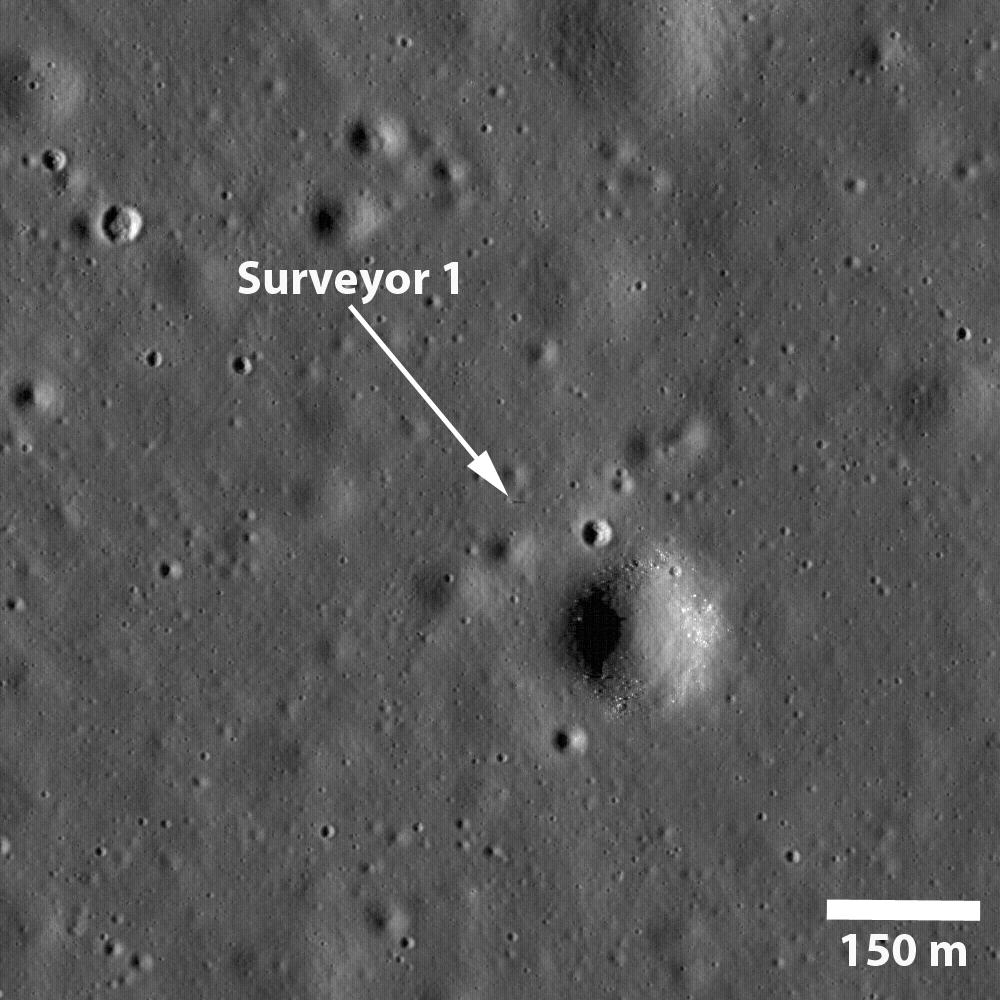

Surveyor 1’s accomplishments paved the way for six more missions over the next year and a half, aimed at exploring the moon. Four of these achieved their goals, highlighting both the challenges and breakthroughs of lunar exploration. Crucially, the data and insights from these missions significantly mitigated the risks of the Apollo 11 moon landing. Today, the Surveyor spacecraft remain on the moon as lasting symbols of human ingenuity.

Following his contributions to Surveyor 1, Montgomery joined the Mariner 6 mission, where he applied his expertise to design a camera system that captured some of the earliest detailed images of Mars during its 1969 flyby.

“I was involved in a lot of beginnings,” he said, highlighting the pioneering nature of his work.

He later returned to the Surveyor program to analyze the components of the Surveyor 3 camera retrieved by Pete Conrad during the Apollo 12 mission. The camera helped assess how temperature extremes affected various components, guiding the selection of more resilient materials for future missions.

Reflecting on Surveyor 1’s global impact, Montgomery shared, “Watching Surveyor 1 land from Goldstone, I realized the significance of our work, but the full extent of its impact only became clear years later. It’s monumental, and I feel a duty to convey the importance of those moments, especially as one of the mission’s few surviving contributors.”

Chronicling the Surveyor mission:

Donald Montgomery’s insights about Surveyor 1 are featured in the Encyclopedia of Lunar Science by Springer, a Swiss publisher. He collaborated with JPL colleague Justin Rennilson and Hughes Aircraft’s Walt McCandless to pen chapters about their experiences as key players on the mission. These contributions were later compiled in “Surveyor Missions,” a book published to commemorate the golden anniversary of the program and the first U.S. soft landing on the moon.

“More than 70 years since I graduated from Cal Poly, and I’m still putting the Learn by Doing philosophy into practice,” Montgomery noted with pride.